By William Godwin

This month is Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month. In honor of the geoscientists living along the “Ring of Fire”, AEG is providing some background on geologic hazards and events that have impacted humans in the Circum-Pacific area.

Japan and the Development of the Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) Systems

On December 7, 2012, a 7.3 magnitude earthquake struck approximately 150 miles offshore of the northeast coast of Japan. Seconds after the first shock wave, notice was sent nationwide of an impending major earthquake. Subsequently, television and radio stations interrupted programming to broadcast the message and warnings. Meanwhile, messages came via text to cellular phones. Thus, Tokyo residents had a full six minutes of warning before they felt the first seismic tremors. As a result, this was the first time an early warning system had been successfully used to warn the public of an imminent major earthquake.

After the devastating 6.9 magnitude Kobe earthquake of 1995 (damage shown in Photo 1 below), Japan invested $1 billion in research and development. The country’s meteorological agency implemented its earthquake early warning systems in December 2007. So, when an earthquake strikes, seismographs near its source detect the first seismic waves. Those are known as primary or “P” waves. P-waves are followed by more powerful secondary “S” waves. “S” waves travel more slowly than P-waves, but with much more potential for damage. The meteorological agency’s computer system analyzes the P-waves and determines if the S-waves are powerful enough to warrant alerting the public and the system issues a warning automatically.

Author By 神戸市, CC BY 2.1 jp, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37241600

It has been 11 years since the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake (Tohoku-Oki earthquake), a Mw9.0 megathrust event in the Japan Trench, which occurred on March 11, 2011. The resulting strong ground shaking and large tsunami caused severe damage in a large part of eastern Japan. The Tohoku-Oki earthquake and subsequent intense seismic activity also shed light on technical limitations of the Japanese nationwide earthquake early warning (EEW) system, which afterwards led to further developments of the system.

Currently, Japan employs the most sophisticated EEW in the world, however other systems are being developed in Mexico and the United States, The USA ShakeAlert earthquake early warning system can save lives and reduce injuries by giving people time to take protective actions like drop, cover and hold on before potentially dangerous earthquake shaking arrives at their location. In addition to supporting public alerts to mobile phones, ShakeAlert system data has, since late 2018, been used to develop applications that trigger automated actions. Automatic actions can be used to slow down trains to prevent derailments, open firehouse doors so they don’t jam shut and close valves to protect water and gas systems.

Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC)

The PTWC serves as the operational warning headquarters for the Pacific Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System. PTWC works closely with other international, sub-regional and national centers in monitoring seismic and sea level stations around the Pacific Ocean for large earthquakes and tsunami waves. The PTWS makes use of about 600 high-quality seismic stations around the world to locate potentially tsunamigenic earthquakes, and accesses about 500 coastal and deep-ocean sea level stations globally to verify the generation and evaluate the severity of a tsunami. The system disseminates tsunami information and warning messages to designated national authorities in over 100 locations across the Pacific. Sub-regional centers provide regional alerts to the U.S.A. west coast, Alaska and Canada, and the northwest Pacific and South China Sea regions, respectively.

A tsunami caused by an earthquake off the coast of Chile travels across the Pacific Ocean and killed 61 people in Hilo, Hawaii, on May 23, 1960. The massive 9.5-magnitude quake had killed thousands in Chile the previous day. The earthquake, involving a severe plate shift, caused a large displacement of water off the coast of southern Chile at 3:11 p.m. Traveling at speeds in excess of 400 miles per hour, the tsunami moved west and north. On the west coast of the United States, the waves caused an estimated $1 million in damages, but were not deadly.

The Pacific Tsunami Warning System, established in 1948 in response to another deadly tsunami, worked properly and warnings were issued to Hawaiians six hours before the wave’s expected arrival. Some people ignored the warnings, however, and others actually headed to the coast in order to view the wave. Arriving only a minute after predicted, the tsunami destroyed Hilo Bay on the island of Hawaii (see photo 2 below). Thirty-five-foot waves bent parking meters to the ground and wiped away most buildings. A 10-ton tractor was swept out to sea. Reports indicate that the 20-ton boulders making up the sea wall were moved 500 feet. Sixty-one people died in Hilo, the worst-hit area of the island chain.

The tsunami continued to race further west across the Pacific. Ten thousand miles away from the earthquake’s epicenter, Japan, despite ample warning time, was not able to warn the people in harm’s way. At about 6 p.m., more than a day after the earthquake, the tsunami struck the Japanese islands of Honshu and Hokkaido. The crushing wave killed 180 people, left 50,000 more homeless and caused $400 million in damages.

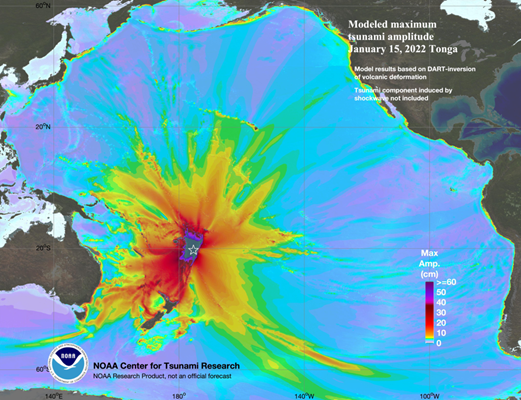

The 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai Eruption and Tsunami

On 20 December 2021, an eruption began on Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai, a submarine volcano in the Tongan archipelago in the southern Pacific Ocean. The eruption reached a very large and powerful climax nearly four weeks later, on 15 January 2022. Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai is 65 km (40 mi) north of Tongatapu, the country's main island, and is part of the highly active Tonga–Kermadec Islands volcanic arc, a subduction zone extending from New Zealand north-northeast to Fiji.

The eruption caused tsunamis in Tonga, Fiji, American Samoa, Vanuatu, and along the Pacific rim, including damaging tsunamis in New Zealand, Japan, the United States, the Russian Far East, Chile, and Peru (as shown on image below). At least four people were killed, some were injured, and some remain possibly missing in Tonga from tsunami waves up to 15 m (49 ft) high. Two people drowned in Peru when a 2 m (6 ft 7 in) wave struck the coast. Preliminary data indicate that the event was probably the largest volcanic eruption in the 21st century, and the largest recorded since the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo. NASA determined that the eruption was "hundreds of times more powerful" than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Regional Geoscience Associations

In addition to the organizations mentioned above, two other international societies provide opportunities to share information and resources

Asia Oceania Geosciences Society (AOGS) was established in 2003 to promote geosciences and its application for the benefit of humanity, specifically in Asia and Oceania and with an overarching approach to global issues. The Asia-Oceania region is particularly vulnerable to natural hazards, accounting for almost 80% human lives lost globally. AOGS is deeply involved in addressing hazard-related issues through improving our understanding of the genesis of hazards through scientific, social and technical approaches.

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Geosciences (AAPIiG) is a grassroots, member-driven organization committed to building a community that supports AAPIs within geosciences. We welcome all geosciences community members who self-identify as Asian American and/or Pacific Islander, as well as individuals of Asian- and/or Pacific Islander-descent working in U.S.-based institutions